Words and photos by John DeLeva

My first published travel article, March 1996

Soloman Naeote is an auto mechanic, but he can't drive to work. He must, by the Spartan rays of a 5 a.m. flash light, navigate a rocky, mule-dung laden foot trail that hugs some of the world's steepest sea cliffs. Along with his akita-lab, Riley, Soloman switchbacks his way underneath a canopy of lush emerald-jade vegetation that rises from the crashing cobalt surf like a breaching humpback. Unfortunately, the stunning beauty of their daily trek is hidden by darkness on the way down and clouded with exhaustion on the way back up. Such is the commute to a settlement called Kalaupapa in a county caled Kalawao, on an isolated section of Hawaii's time-gone-by island of Molokai.

Kaiawao County is a place that Honolulu librarians, Maui map merchants, state legislators, even the almanac, couldn't place by name. Say "leper colony" however, and they all know what your looking for. But that subject must go on hold for a second, while the importance of Kalawao being a county is explained. Last summer I concluded a 10-year quest to visit every county, borough, and parish in America - all 3,086. I didn‘t venture to Kalawao County though, because technically it isn't a county anymore. The Maui County clerk handles its ballots for state and federal elections (Kalawao had no elected officials) while it is administered by Hawaii's Department of Health. Still, my quest didn't feel complete. I wanted certainty, not technicalities.

A few friends got together and we took to Solomon's trail. At rock bottom we joined a few mule riders and small plane flyers to board a barged-in school bus operated by Father Damien Tours. Leading us aboard was a man wearing an aloha shirt and a leathered Chinese-Hawaiian complexion. A 54-year resident of Kalawao County, Jimmy Brade answered many questions we would probably have been afraid to ask. We learned how victims of the dreaded disease weren't just stigmatized and segregated, but apprehended and isolated by decree of King Kamehameha V in 1865. Literally stolen from the clutch of family members, those thought to have leprosy were thrown into cages, placed on a barge and shipped to Kalawao.

Tossed overboard in crashing surf, early victims were, like garbage, left to float aimlessly, or make shore and rot. It was the ultimate dichotomy: a human hell in a heavenly setting. There were no doctors or medical supplies in the early years at Kalaupapa. Victims, with ulcerated and distorted faces, decaying bones, and deformed fingers and toes, had only one friend: early death. That was, until the guy who got his name on the bus arrived.

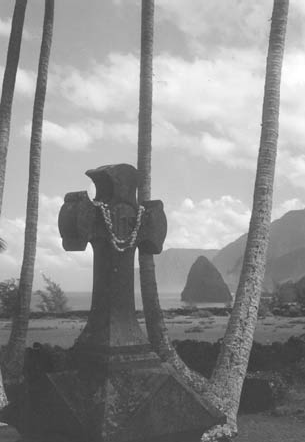

Joseph de Veuster, known as Father Damien, left the Belgian countryside as a missionary of the Congregation of Sacred Hearts. He arrived in a place where exiled souls lived lawlessly while waiting to die. But Damien's attitude altered almost everything. He didn't arrive just to work with the patients, he came to live, love and inevitably die with them. With unbridled devotion, he broke all the rules of common sense to show the terminally sick that someone cared unconditionally. Damien brought hope, but not a cure. It was 57 years after de Veuster departed - more than a half-century of using victims as human guinea pigs - that the miracle known as sulfone antibiotics arrived. Jimmy Brade was one of those guinea pigs. "When I arrived here in 1942 they told me I had ten years to live." Jimmy exclaimed. “I've been here over 50 years now and I'm proud to say that no other generation will have to experience the dreadful isolation and separation that we did."

Leprosy went from terminal to outpatient status and Hawaii abolished isolation legislation. In 1969 Kalawao residents could legally leave. Ironically, to this day, some never have. Not Jimmy and his wife. Cordoned to 11 square miles for 62 years, they made up for lost time. One particular place draws them four times a year. "Vegas, we love Vegas," Jimmy said wilh a big grin. But then winning $30,000 at keno one night could make anyone love the Nevada desert.

Today Kalaupapa is a National Historic Landmark, dedicated to letting its last 64 residents live out their lives comfortably. We toured the well-groomed grounds, awestruck by the setting, astonished by more of Jimmy’s stories. We made an extended stop at a book store that serves double-duty as a museum. There we had a chance to meet Jimmy’s "gift from God," his wife Nancy. A resident of Kalapapua since 1936, she was the one that Jimmy had deferred to earlier when I popped the big question.

Like a helpful librarian ready to answer anything, Nancy smiled and nonchalantly responded to my question. "Kalawao, of course we're a county. Not many people know that though." How right she was, not legislators, map merchants or the almanac: heck, not even a guy who thought he had counted them all.